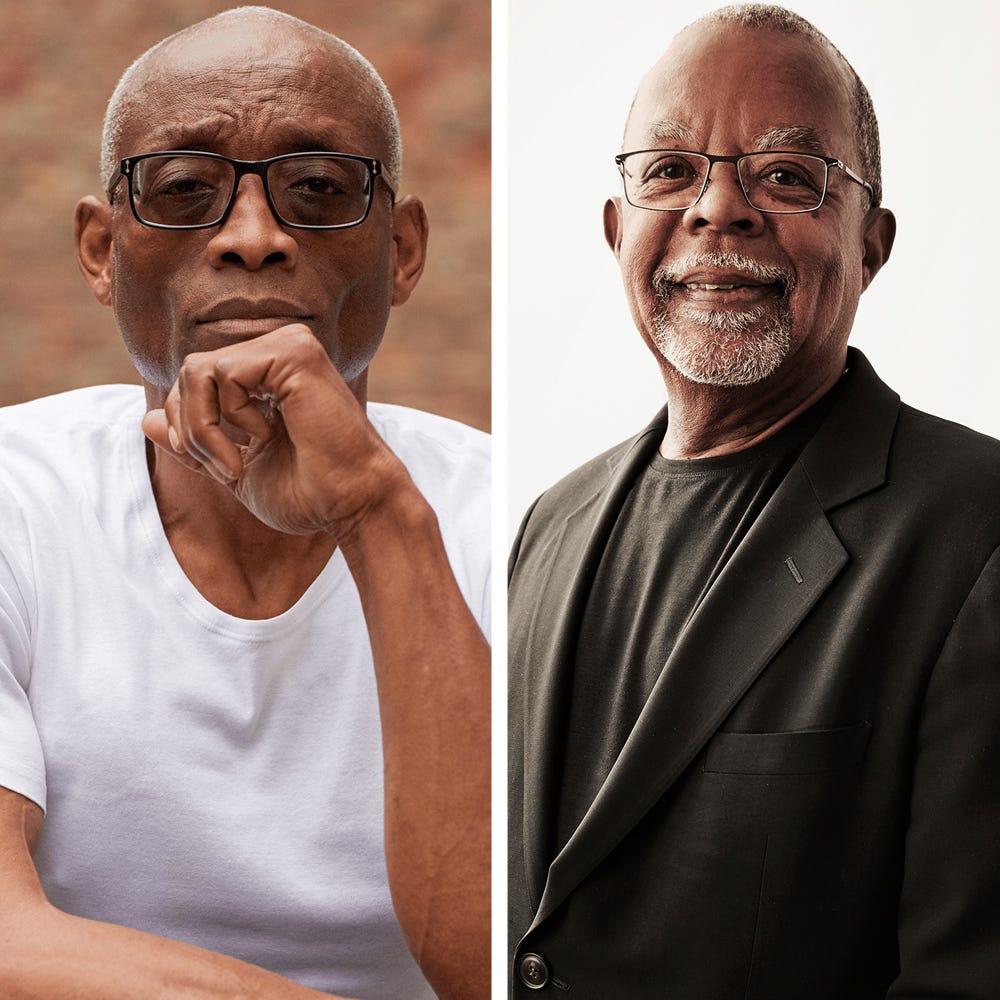

Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Bill T. Jones first met in 1994, when Gates, then early in his career as a professor at Harvard, was writing a profile on the dancer and choreographer, who was at the height of his career. Nearly 30 years later, the two have remained friends and continue to set—and then exceed—the pace within artistic and intellectual spaces.

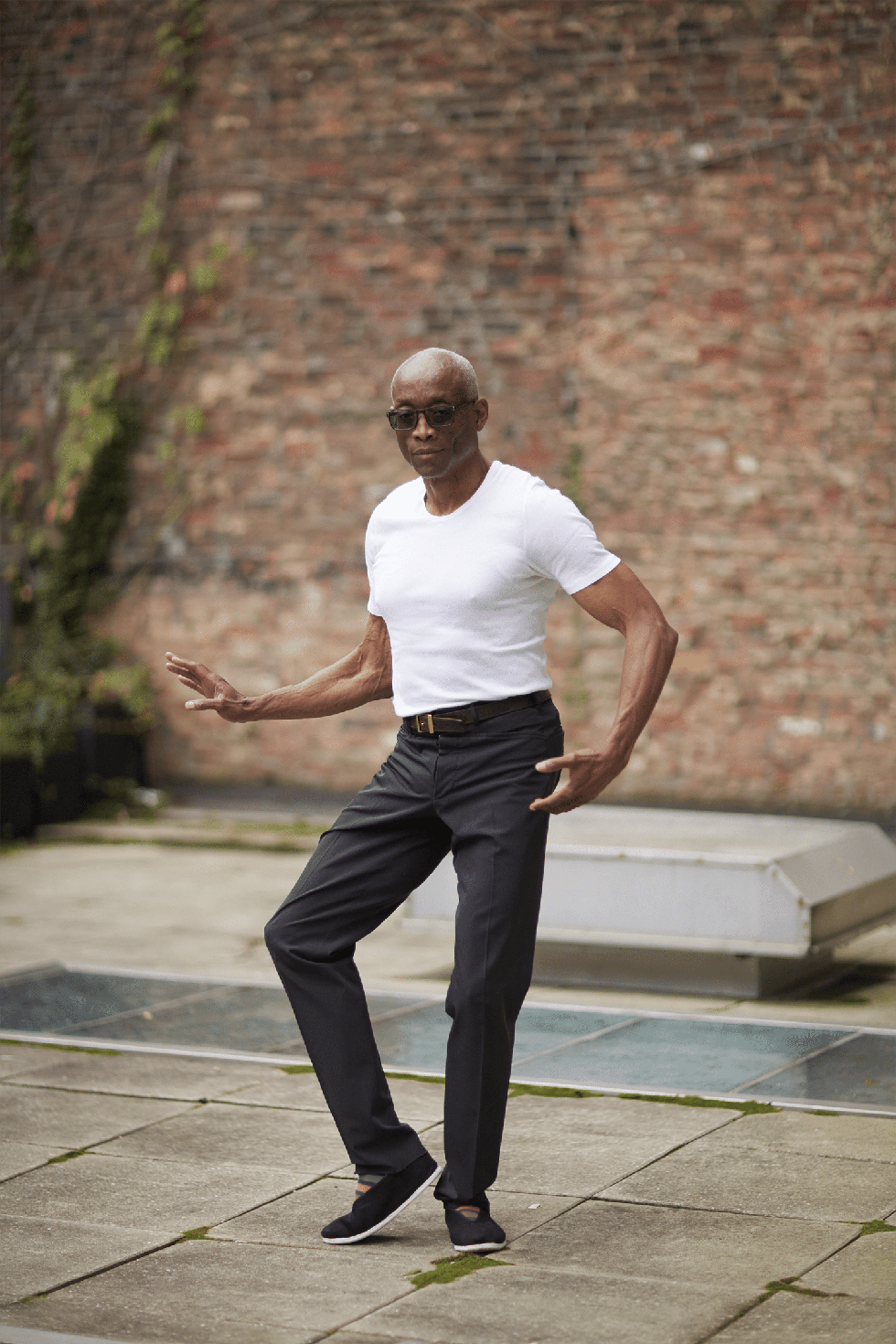

Jones and his partner in life and dance, Arnie Zane, began performing together in the early 1970s. In 1982, they founded the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company, assembling a nontraditional group of dancers of all ethnicities, sizes, and backgrounds to perform their groundbreaking works, which rejected the more restrictive styles of classic modern dance and incorporated film, singing, and spoken dialogue. Shepherding a new type of postmodern dance, they commented on topics like identity, censorship, homophobia, and narratives surrounding the Black male body through raw, emotive choreography that often saw male dancers performing sensual duets.

In 1988, Zane died of AIDS-related lymphoma, and the experience of watching his partner’s suffering inspired Jones to choreograph his most well-known piece to date, the controversial Still/Here (1994), which included videotaped interviews with individuals dying from AIDS and cancer. Throughout his career, Jones has also collaborated with a number of other companies, including Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and choreographed the Broadway musicals Spring Awakening (2006) and Fela! (2009), for which he won Tony awards.

More From Harper's BAZAAR

As an award-winning literary critic, historian, scholar, filmmaker, author, and director of Harvard University’s Hutchins Center for African & African American Research, Gates has worked tirelessly to expand the study and recognition of Black literature and culture. In addition to rediscovering some of the earliest novels by African Americans, he’s written or cowritten more than 20 books of his own and produced and presented an astounding 26 documentary films, including 2013’s Emmy-winning The African Americans. Since 2012, he has hosted the PBS series Finding Your Roots With Henry Louis Gates, Jr., in which, with the use of DNA testing, he helps celebrity guests discover—and face—their ancestral histories.

Jones and Gates recently connected to consider what it means to build artistic legacies as Black men in America.

Henry Louis Gates Jr.: Bill, I know that you were forced to think about legacy with the passing of Arnie in 1988. One of the most touching things about your career is the fact that the dance company was named the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company.

Bill T. Jones: I think I should first own up to the fact that I am not a member of the elite art practice in our cultural consciousness. Elite art practice would be the ballet or the symphony orchestra. Arnie and I purposely entered into that world because we were still living a certain dream of the counterculture, where the status quo is not your friend. We were homosexuals, and we came onto the scene just a few years after the Stonewall Uprising. So it was “Who are you to think you’re going to have a legacy? And what for? You didn’t come from Martha Graham or Merce Cunningham.” Everyone was convinced that we were a flash in the pan. By pure tenacity, we stayed in there, and then history came to our door when they needed people to talk about the tragedy of HIV and AIDS. … Our work is taught in universities now, and there are generations of people who have come behind us who are challenging or emulating what we did. That is the legacy.

HLG: You said that history knocked on your door, but, Bill, you knocked on history’s door too. The first time I saw you perform, I couldn’t believe it. I was struck at how you were defining the moment of postmodernism with the movements of your body; I saw you very much in the tradition of dance but at a seminal moment when you were redefining it in your own image. … I have a PhD in English literature from the University of Cambridge. But I didn’t want to write about Shakespeare or Milton. I wanted to be part of a generation that would institutionalize the study of people of color, more specifically people of African descent. Something that’s characterized my administration at Harvard, building the African and African American Studies department, is that if the best candidate is white, if the best candidate is Asian, we’re going to hire the white candidate or the Asian candidate. You don’t have to be Black to be an expert on the African American experience. It is just like every other academic field.

BTJ: I don’t think an artist’s credibility rides on their understanding of history. Those criteria of what you call excellence were the headwinds that Arnie and I ran against. People would ask, “Why is this person on the stage at the Kennedy Center? Is this liberal guilt?” So there’s a distinction there when we talk about excellence.

HLG: Many of the greatest scholars of what we now call African American studies had to write their PhD dissertations on a white author or a white subject because it was thought that a Black subject wasn’t worthy in allowing potential scholars to demonstrate that they had mastery of their field. I wrote one of my first books, The Signifying Monkey, which is about the Black vernacular tradition, when I came up for tenure at Yale, and I didn’t get tenure. People said, “This stuff is not literature; he’s not ready.” I had taught at Yale nine years. It broke my heart, but I left. Still, I wouldn’t do it any other way. You have to stand up for your principles. I love the Black tradition because I know how rich and vibrant it is. Our people created one of the world’s greatest cultures collectively on the sub-Saharan African continent and in the New World. And the academic establishment traduced it, mocked it, minimized it. But my generation of scholars was able to have an institutional presence in the American Academy. So my goal’s been to defend the culture itself from racists and show, using rigorous methodology, that it is just as sophisticated as any culture in the world.

BTJ: I see why you’re the man for the job there at Harvard. … The famous No Manifesto [1965] of dancer and choreographer Yvonne Rainer, who was the great architect of the postmodern, finished a series of essays with her manifesto, which [says] things like no to moving or being moved, no to audience manipulation, no to virtuosity, no to charisma. A whole generation of people thought, “Wow, that means that she’s saying yes to everything else.” The avant-garde taught us that there was no longer a criteria, but now we’re once again back to this idea of excellence. Can you be a leader in the development of a culture and not have those foundations? Can Jackson Pollock be allowed to throw that paint if he cannot paint like Leonardo da Vinci? Yes, he can. So as we’re talking one Black man to another, do we as Blacks have to be conservative? That’s what I was told. Don’t get out there and embarrass us. But the white kids can get out there and take a crap on the floor and it’s a profound gesture. I wanted to have the ability to be as free as James Joyce. And yet, by the same token, I wanted to be prized for my intellectual understanding. Do you have any feeling about the white avant-garde and the authentic Black self?

HLG: You can’t write a sentence unless you know the ABCs of the syntactical structure in English. You need to learn the ABCs of your profession. And then beyond that, if you’re going to bend a tradition, step outside of a tradition, you need to know the tradition you’re bending or stepping outside of. You didn’t just drop down from the moon. You had studied the history of dance. You knew what would work, what you could take from that history, and what didn’t work and how you wanted to step around it. Miles Davis comes out of a tradition of playing the trumpet.

BTJ: Yeah, but he was a classically trained musician, wasn’t he?

HLG: Yes, he went to Juilliard. And you’re classically trained. He had two traditions that he had to master: the tradition of his classical training and the tradition of the jazz trumpet. And he took those two and braided them and produced his own version. But the point of genius is that you take that training, you imbibe the traditions, the logic, and then you step inside of it to redefine it. Some people will hail you as a genius. Some people will hail you as being the opposite. And that’s when you have to be sustained by self-love that you’ve taken from the people who love you. You have to be able to look in the mirror and say, “I know that I’m right, and I’m ahead of the curve. The world will catch up with me sooner or later.” And that’s certainly the case with you. … One of the reasons I think the most sublime achievements in African and African American culture traditionally have been vernacular forms is that Black people didn’t care what white people thought. When they were inventing ragtime or jazz or the classic blues, they didn’t do it for a white audience.

BTJ: Sometimes Black people can be oppressively conventional in what they think is most high and most beautiful. Young avant-garde white kids run out there, get hit by traffic oftentimes, but they feel they have the right to do it unfettered. It’s more difficult to be a Black person running out there in the traffic of culture with them.

HLG: You are absolutely right that, traditionally, Black culture has been conservative. And it was conservative because of fear of acceptance or ridicule, right? But the element of Black culture makers who weren’t conservative was real people who were just inventing the culture that they loved in juke joints and drawing on the traditions in which they were working.

BTJ: Do you think that speaking about race as two Black intellectuals is something that we are programmed to do at this point?

HLG: That’s the burden of representation. When is Bill T. Jones an individual? When is he Black? When does your responsibility to your own integrity start and stop in a heavily burdened political context? Are you completely free of the white gaze? Is that ever possible? And I would say it’s more possible for us today than it’s ever been for Black people in North America. And as long

as the overwhelming number of the people in prison are Black, as long as the amount of wealth that our people have accrued is so sadly small, then, yeah, we still have obligations to the African American community. But our responsibility is not to allow the community to confine the contours of our imagination. That is very important for us to always remember.