For 55 years, the historic photo of the men pointing at the late Dr. Martin Luther King’s assailant on the roof near the Lorraine Motel has encapsulated one of the darkest moments of the civil-rights movement.

Since she was a little girl, Leta McCollough Seletzky always knew that her father, Marrell “Mac” McCollough, was in the era-defining photograph. But in 1993, as she became a politically aware teen, she was taken aback when she read an article in the Memphis Commercial Appeal about the very same man who held a bleeding King being undercover with the Memphis Police Department to infiltrate a local Black militant organization akin to the Black Panthers, the Invaders.

Too young to unpack these complexities, Seletzky eventually left Memphis and attended law school. But she always questioned her father’s involvement in the story. Eventually, she wrote The Kneeling Man: My Father’s Life as a Black Spy Who Witnessed the Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., which was published this April, 55 years after King’s murder.

More From Harper's BAZAAR

The Kneeling Man details Seletzky’s relationship with her father, his interactions with Dr. King, the Tyre Nichols police killing in Memphis, and ongoing police violence in America. She speaks with Bazaar.com below.

What did your father tell you about the day Dr. King was assassinated?

He told me about how that day, April 4, 1968, he was in his role as [a double agent for the Memphis Police Department] with the Invaders as their Minister of Transportation because he was one of the few members who had a car. And so he was driving around one of Dr. King’s cohorts named James Orange and the [members of the] SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference]. They called him Baby Jesus, and he wanted a pair of four-button overalls to wear to this march that Dr. King was supposed to lead. They went all over Memphis looking for these four-button overalls, and so at the end of the day, they went back to Claiborne’s Temple, which was one of the nerve centers of the sanitation-strike supporters, and picked up James Bevel. [Then they all] went over to the Lorraine Motel, which was one of the bases of operation for the SCLC while they were in Memphis, supporting the strike.

There was kind of a small crowd gathered around underneath the balcony, and Dr. King was leaning on the railing. It was only shortly after my dad arrived that the shot rang out. My dad, having been a military police officer, plus having been through the police academy—unbeknownst to the people who were with him—he knew first aid. He ran up there to try to give him first aid in an active-shooter situation, which, by the way, wouldn’t be most people’s instinct. He told me in very great detail about what happened when he ran up there and how he tried to stop the bleeding.

My father—when he went back home after that day, he had blood all over the front of his pullover. He described, in intimate detail, going home, taking off the pullover, folding it up, and putting it aside because he knew that that was something that the FBI was going to want.

Why did your father become a police officer?

Well, funnily enough, that wasn’t something that he set out to do. But he was part of this pipeline that often catches Black people and people who are lower income, from high school to the military. That was the only way that he was going to be able to pay for higher education, through the GI Bill. He took the entrance exam when he was inducted into the Army, and he was placed in the military police. He did that for three years. He got out of the Army, went to Memphis, where he had some relatives, and thought there would be some opportunity to work.

My dad and his cousin Eugene were riding in the car one morning, listening to the radio, as they always did. And then a recruiting ad for the Memphis Police Department came on. And so Eugene said, “Hey, Mack, weren’t you police in the military? You got to go apply for that.” And my dad said, “You know, they aren’t hiring Negroes.” And Eugene said, “You don’t know that. You ought to just go try.” And so he went down there to apply because he didn’t want to disappoint Eugene.

As your father went on to become a double agent for the Memphis Police Department, how did he feel about what he was doing?

I often would ask him how he felt about things, and he was very disconnected from that. My take on it is he compartmentalized what his personal feelings were and his sympathies there. And on the other hand, his professional duty was to maintain his job, and that was something he was well trained to do, coming out of the military, where it’s not about how you feel about these orders that you’re given; you just follow the orders. And similarly, in the Memphis Police Department, he was doing this job that he thought, If there’s a concern in law enforcement, that the Invaders might be doing things to cause disorder in the streets, then I will have no problem listening in to find that out. In other words, his role was to observe and listen to what was happening and report it back. He did that with honors, as far as he was concerned. And he reported back the truth of what he observed, which was that the Invaders were not a danger to civil order in Memphis.

I think it’s an example of double consciousness as articulated by WEB DuBois, where you have this conflict between identity as a Black person and then identity as an American. And I think it’s very much graphically illustrated by his literal assumption of two identities as Marrell the Invader and then of course his real identity as Mac the police officer. As far as his personal feelings went, he greatly admired Dr. King and the civil-rights movement. He fully supported these things. He also supported the sanitation strike, and he thought the sanitation workers were being exploited and the city wasn’t treating them right. But to him, that was separate and apart from the duty.

Did he ever feel as if he was being used?

Looking back, that’s something that I see as an exploitative situation, because here he is a 23-year-old guy fresh out of the police academy; he had just graduated in December 1967. The sanitation strike happens in February 1968, so this is really just a matter of months. And mind you, this was dangerous in the sense that the police department had no idea what they were doing, and you get the feeling that, on some level, they were not terribly concerned with his personal safety, because it was already known to many people that he was a police officer. He had been in the newspaper in a full photo spread as someone who was in the police academy. And he was also in the newspaper another time as a commissioned officer because he was involved in this incident where there was a shooting; he and his partner shot at youth and actually hit one. His first assignment after graduating from the police academy was to do foot patrol in uniform in one of the busiest shopping centers in town. He did car patrols in two of the major Black neighborhoods in Memphis. Many, many people saw him in uniform.

I just don’t think that he had the perspective to see the implications of what he was getting into. And I think there’s a lot of naivete to his decision.

In January 2023, Tyre Nichols was allegedly murdered by three Black Memphis police officers. His killing was caught on camera and led to the rare instance of an indictment against police. Are there any similarities to this instance that your father alluded to that are in The Kneeling Man? Particularly in regards to the white officer who avoided much of the media attention?

That dynamic reminded me of a person in my book who was one of Memphis’s first Black officers. And this was back when, you know, there had been a hue and cry over police brutality in Memphis—maybe the 1940s. Black officers were restricted in where they could patrol, so they could only patrol these Black neighborhoods. This officer would patrol down around Beale Street. And the officer—not my father—would brag about how he brutalized Black people. And he would say, in front of my dad’s white partner, “I’ll go up beside a knucklehead so quick,” and laugh about it, and the white officer thought it was funny. This white officer would take this older Black officer on ride alongs with my dad when he was fresh out of the academy, and it was a way of this white officer showing my dad what was expected of him as a Black officer and what his role was, which was to brutalize Black people. So, to me, these guys are an expression of that: There you have a Black person who is carrying out the ends of a violent and oppressive and white-supremacist status quo.

I think that it is an expression of our society’s tendency to pin blame on Black people, to be disproportionately critical and punitive of Black people, you know? Not to say that these officers don’t deserve every bit of accountability. But that does not mean that white people shouldn't face the same accountability. Right? That’s the problem.

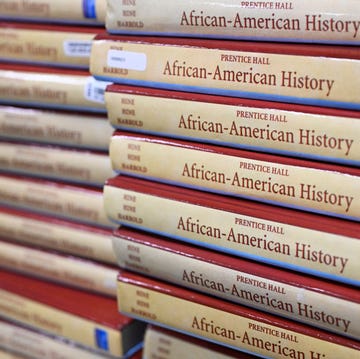

At a time when Republicans across the country are banning books and stomping out women’s rights and racists have practically turned woke into a slur, could you talk about how the timing of this book fits into where we’re at in the U.S.?

In order to understand this present moment that we’re in, we’ve got to understand the historical context. And this book is historical context for where we are as Black Americans. This is not an explainer about where we are. This is an illustration. That is why people are banning books in the first place. Because when you have a narrative that doesn’t just explain but shows how white supremacy serves to rob people of the promises contained in the founding documents of this country and serves to oppress people in very insidious ways, it’s harder to perpetuate those harms.

How did you emotionally prepare for writing this story?

I spent most of my life running from the stories because of the silence about it in my family. My father never talked about what happened other than he had to cooperate with the congressional investigation about Dr. King’s assassination back in the ’70s. Other than that, he didn’t really talk about it. He kept it inside.

What tends to happen when you have any kind of vacuum, like in nature, it fills up with something else. And so for me, what I filled up with was kind of unease that gradually became fear and then a dread as I learned more and more of his presence there.

It was only when I had my children that I had a moment to kind of step back and really sit with my life and my thoughts. What was going on underneath the surface? What am I going to tell them about their grandfather? Do I want to pass it down to them? This legacy of silence and dread that I’m carrying? It just felt wrong.

Mark Braboy is a Chicago bred music and culture journalist, writer, photographer, and editor.