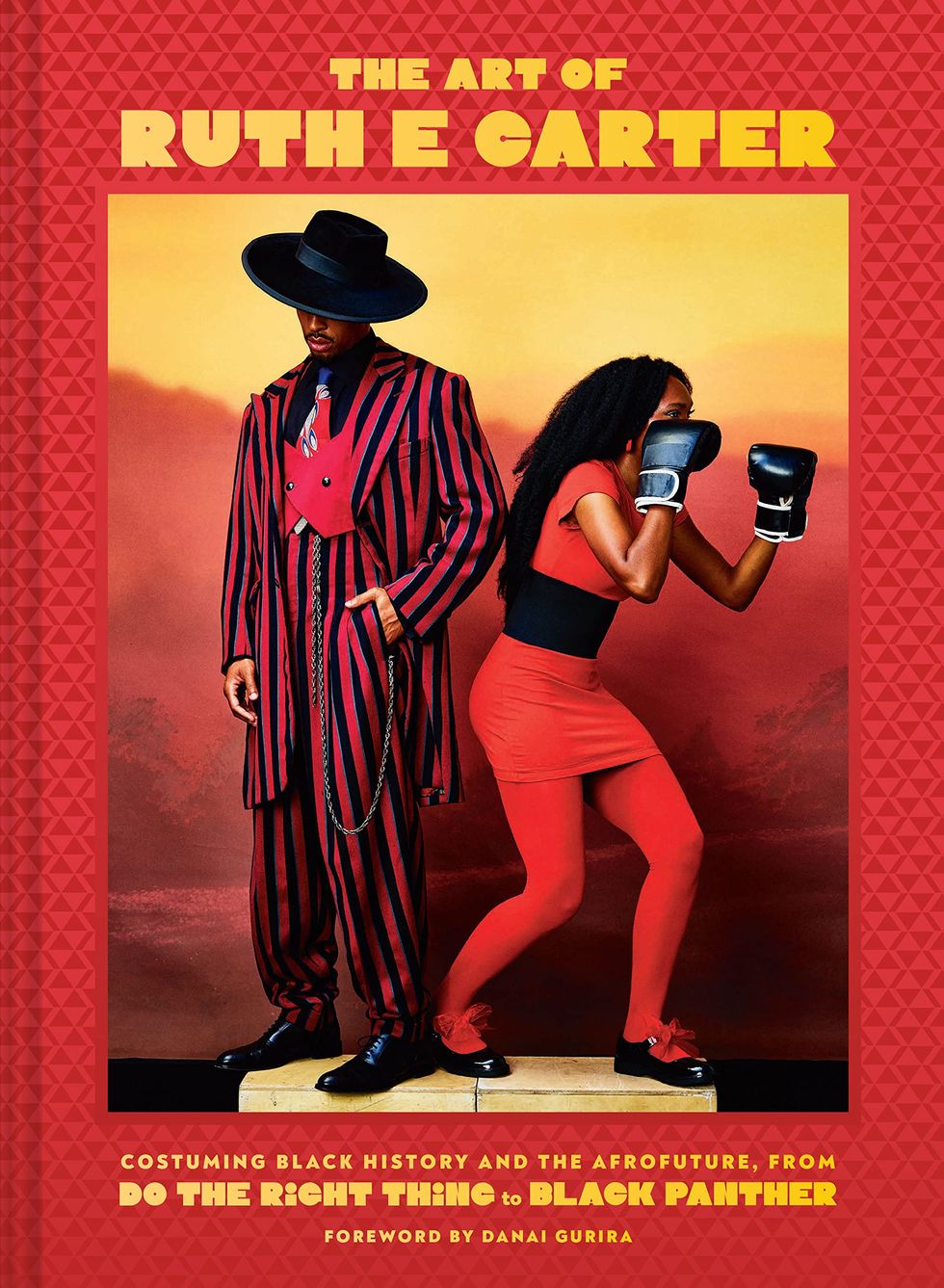

Before Ruth E. Carter made history as the first Black woman to win two Academy Awards (regardless of category), she was known as one of Hollywood’s most invaluable fashion forces. Her costume work is associated with some of the most formative Black films of our time—from Spike Lee’s 1988 musical comedy School Daze to her most recent blockbuster, Black Panther: Wakanda Forever—and is now commemorated in her first book, The Art of Ruth E. Carter: Costuming Black History and the Afrofuture, from Do the Right Thing to Black Panther. Ahead, read an official excerpt from the groundbreaking costume designer’s definitive tome.

A year after successfully meeting the many challenges on Spike Lee’s first studio film, School Daze, I returned, by Spike’s invitation, to Brooklyn’s own 40 Acres and a Mule to talk about beginning his latest work, Do the Right Thing. It was exciting to pair up with Spike again. I had hoped that he thought I did a good job and wanted me back. Spike is very hands-on when it comes to the who, what, where, and how of his projects. If you are participating, it is because he said so. I marveled at the fact that he wrote the first draft of the script in just two weeks! He also boasted about it. I guess that’s how I knew. But I took that in and thought of him as this maverick. And I especially wanted to know about the costumes he would ask me to create for the film, set in his childhood home—a place I had grown to love as well.

Spike and I used to walk from his 40 Acres office, housed in the restored firehouse on DeKalb Avenue, to a local café or restaurant to talk about our issues from the last film, easing unresolved tensions, like who was stealing the Nikes from our warehouse. Usually, the issues had to do with not having enough multiples of a certain costume to shoot a scene. None of it seemed to matter as much anymore. Now we had a brand-new script and a new story to craft. It was nice to sit and have lunch with Spike. Our meeting went well, because we were far removed from the intensity of being on the set.

More From Harper's BAZAAR

I really don’t remember at all what I had on my plate that day; I remember more that Spike was generous and human. That first film experience had left me with feelings of not measuring up to Spike’s standards. He was the only filmmaker I knew at the time. Now, returning felt like being a part of the winning team. We quickly left the past behind and moved onward, discussing the details.

Spike sat across the table, looking down into his handwritten address book, and spewed off the personal telephone numbers of the cast he’d chosen for the film: John Turturro, Rosie Perez, Bill Nunn, and others, some of whom seemed to be personal friends of Spike’s. “Here. Take this number down. That’s John Turturro. Call him today. He has some ideas for his costume.”

My first script note was: “It’s the hottest day of the summer.” Instructions from Spike: “This film is going to have to look hot! Everybody is sweaty. And you know, in Nueva York when the weather is hot, when the temperature is up, up, up, the tempers run high, high, high.” Then he let out a whale of a laugh. We were making a protest film. It was addressing some of the racial tensions that had recently played out in Brooklyn and the surrounding neighborhoods. The political climate of New York in the late ’80s and early ’90s, with multiple racial incidents against Black people, having the first Black mayor, the Howard Beach incident, and the Tawana Brawley hearing, all gave people a reason to be roused up. This was the impetus of the story. And Spike was clear: Tawana told the truth, Iron Mike Tyson was Brooklyn’s finest, and Public Enemy would write the protest song for the film.

How would we make it a neighborhood? How would we keep the story real as it eventually erupts into a riot? “Also, the cast will need to look sweaty and wear lots of summer shorts and summer tops!” Spike spewed. He wanted me to make special crop tops and midriffs for the ladies and basketball shorts for the men. We walked around the set all day with spray bottles filled with glycerin and water, spraying people under the arms and on the chest. This was great in June and July. But when the fall started to creep in during late August, the cast really felt the chill.

Second note from Spike: “4-finger love-hate rings, a must.” It was written in the script. I had no idea where to get them made. I had a local guy make a prototype, and it really looked bad. Then Spike said, “Go to one of the jewelry stores over in the Fulton Mall.” A few weeks later, from right there down the street from the office, arrived two beautiful sets of love-hate brass knuckles for Radio Raheem.

The leather necklaces worn by Buggin Out were also requested by Spike. It was in style to wear something African in Brooklyn and Harlem. Culture was everywhere. But it was truly in direct opposition to the massive amounts of gold being worn by many other urban youths, especially Black inner-city kids. Spike would have none of that. Instead, he insisted on these handwoven necklaces, which were purchased off the tables of street vendors from Brooklyn to Harlem. They were very popular. Giancarlo Esposito, the actor who played Buggin Out, added his own personal crystals to his collection of necklaces.

The trust and camaraderie at the beginning of a new adventure with Spike Lee was priceless. There were many logistical challenges in costuming the film, which takes place over the course of a single day. How do we shoot the same costumes that people would wear every day, for fifty-five days of shooting? There would be an opportunity for the characters to change clothes only after the fire hydrant was opened. This water scene required aqua socks for the shooting crew. Also, we needed to use Nike’s product placement as a resource since we would have to make the film on a tight budget. The Nike apparel came in very handy. They gave us plenty—not only the sporty looks of compression shorts under regular basketball shorts, but also aqua socks and sneaker after sneaker.

But the Nike apparel was very bright. Glance in any direction around the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, the setting of our film, and there was a different message and color story. Then, you notice the layers of socioeconomics, strife, cultural expression, and muted tones. And it was very unusual for a Brooklyn neighborhood to wear that much Nike at one time, on one block. I knew that all this bright Nike product placement had to work within the storyline and color palette. It was challenging. So, I started to create outfits out of African cloth that were equally vibrant and saturated, to balance the colors of the Nike products and to inject the cultural realism that I knew of as Brooklyn into the costumes. African inspiration was a daily occurrence, with women and men wearing African patterns. Brooklyn was a place where cultural garb was a way of life.

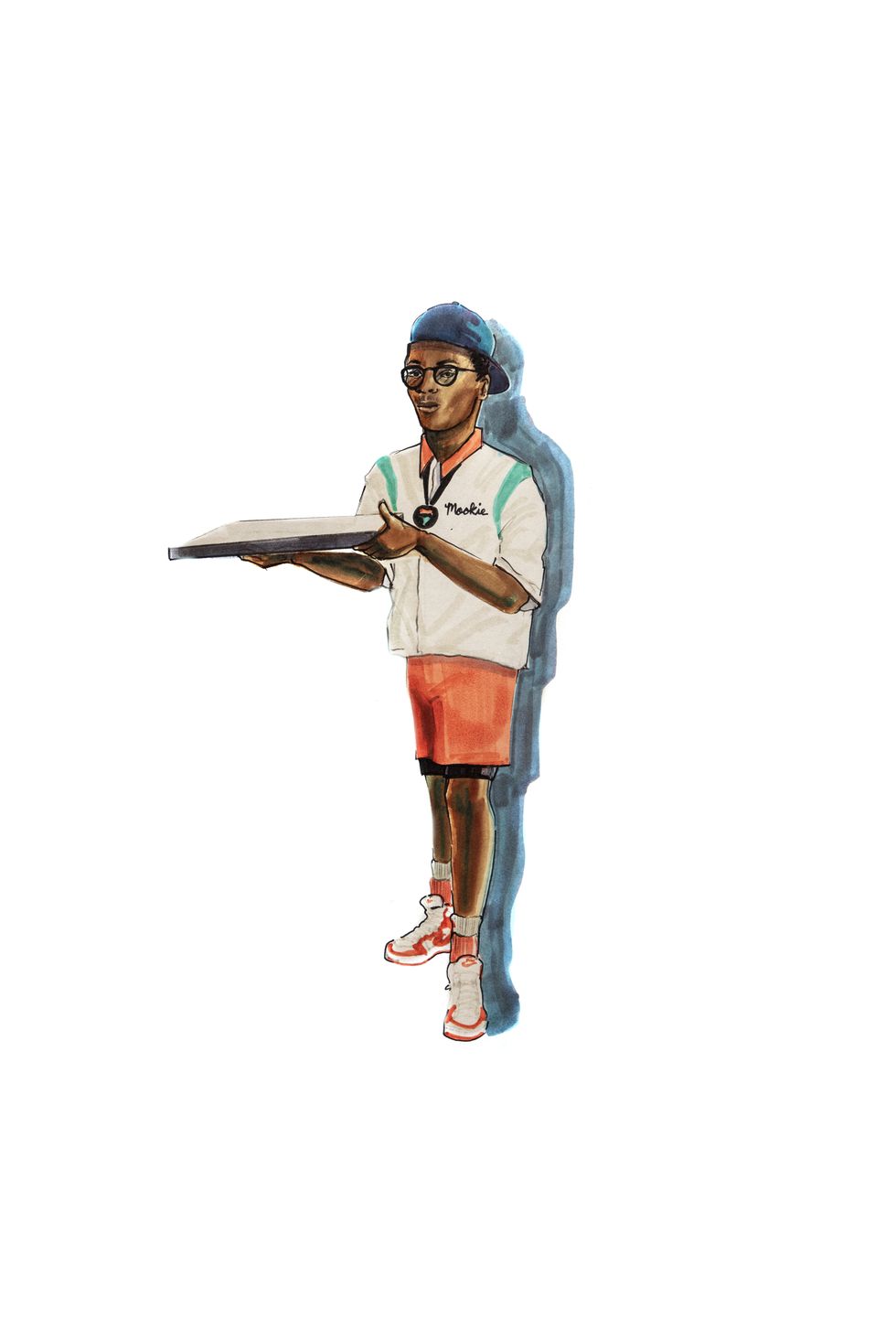

Mookie, Spike Lee

The Jackie Robinson jersey was Mookie’s first costume (he wears two in one day), bought and paid for by Spike Lee himself. He handed it to me one day, saying, “I’m gonna wear this.” There was only one of this jersey, so I didn’t want to use it during the riot or water scenes.

Mookie’s second look was a bowling shirt in the colors of the Italian flag: red, green, and white. This idea came directly from Spike. I chose the style and embroidered “Sals Famous Pizzária” on the back. He wore compression shorts that were yellow and green, underneath cotton basketball shorts. The colors of his socks—also yellow and green—coordinated with the whole outfit. And, of course, he was to wear Nike shoes handed to me by Spike himself: Air Trainer 3 Medicine Balls. Mookie’s watch was a little red car that he wore on his wrist. I thought of him as the catalyst of the story—he’s connected to everyone, feeding them conversation and pizza.

Sal, Pino, and Vito, Danny Aiello, John Turturro, Richard Edson

Sal and his sons arrive at Sals Famous Pizzária, the neighborhood pizza parlor, in a big white El Dorado. Pino, the eldest son, is dressed to the nines. John Turturro expressed to me that he wanted his costume to separate him from everyone else and to be black. Pino arrives in black silk and changes clothes into his uniform: white apron, white tank top. This story was about the tensions between races that ignites beyond the heat.

Vito, the younger son, has developed friendships in the Black neighborhood. He arrives at Sal’s in his summer B-boy shorts and doesn’t change his clothes that day.

But Sal changes out of a cactus-print Hawaiian shirt and into a long-sleeve green cotton L.L. Bean shirt. Now, they are ready for the big trouble to come.

The whole neighborhood enters Sal’s for pizza at some point. The colors they wear are in direct opposition to the black-and-white photographs on the wall.

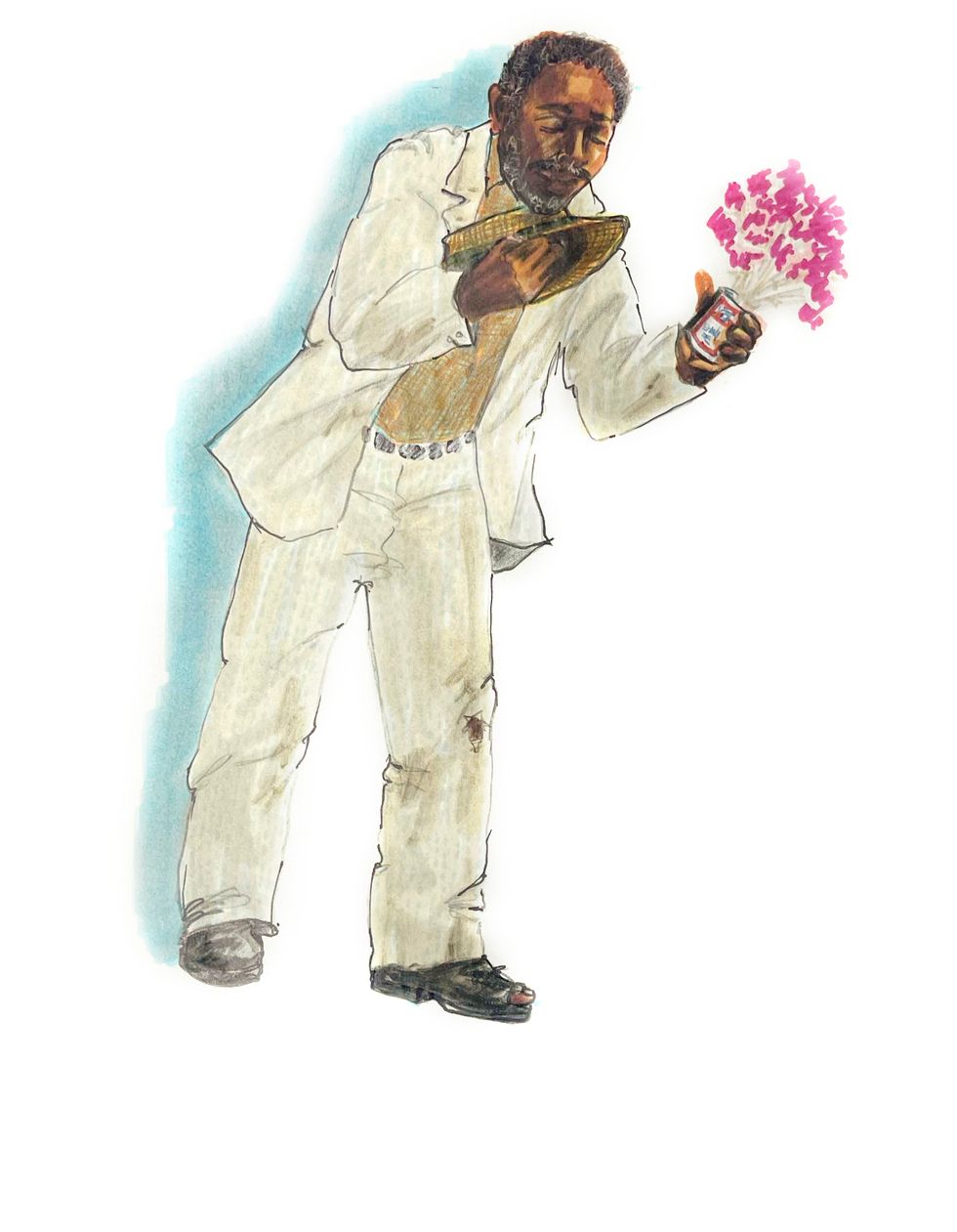

Da Mayor, Ossie Davis

Da Mayor wakes up and proclaims, “It’s hot!” When early mornings are hot, it’s a warning that something crazy is about to happen. The mayor hustles down to Sal’s Famous to sweep the front walk for small change. I put Da Mayor in a seersucker suit that I aged down. My days in theater inspired me to create a costume for him that was artistic and imbued with a story. It would be poetic, telling his past and a bit about his lifestyle. Since he lived in an apartment and wasn’t homeless, I wanted him to present himself as someone of importance, hence the suit. And even though his bout with aging and alcoholism was very apparent, he was known as “Da Mayor” to the whole neighborhood. He was proud as he stumbled after tipping his hat. It was imperative that Da Mayor also look like an unforgettable presence on the block. I exploded a pin in his pockets and filled them with rocks to show wear. I gave him very inexpensive shoes, and I faded his color palette to near transparent in opposition to the extremely vibrant and saturated palette worn by the youths on the block. Somehow, the heat and the vibrant colors all belonged to the younger generation in the film.

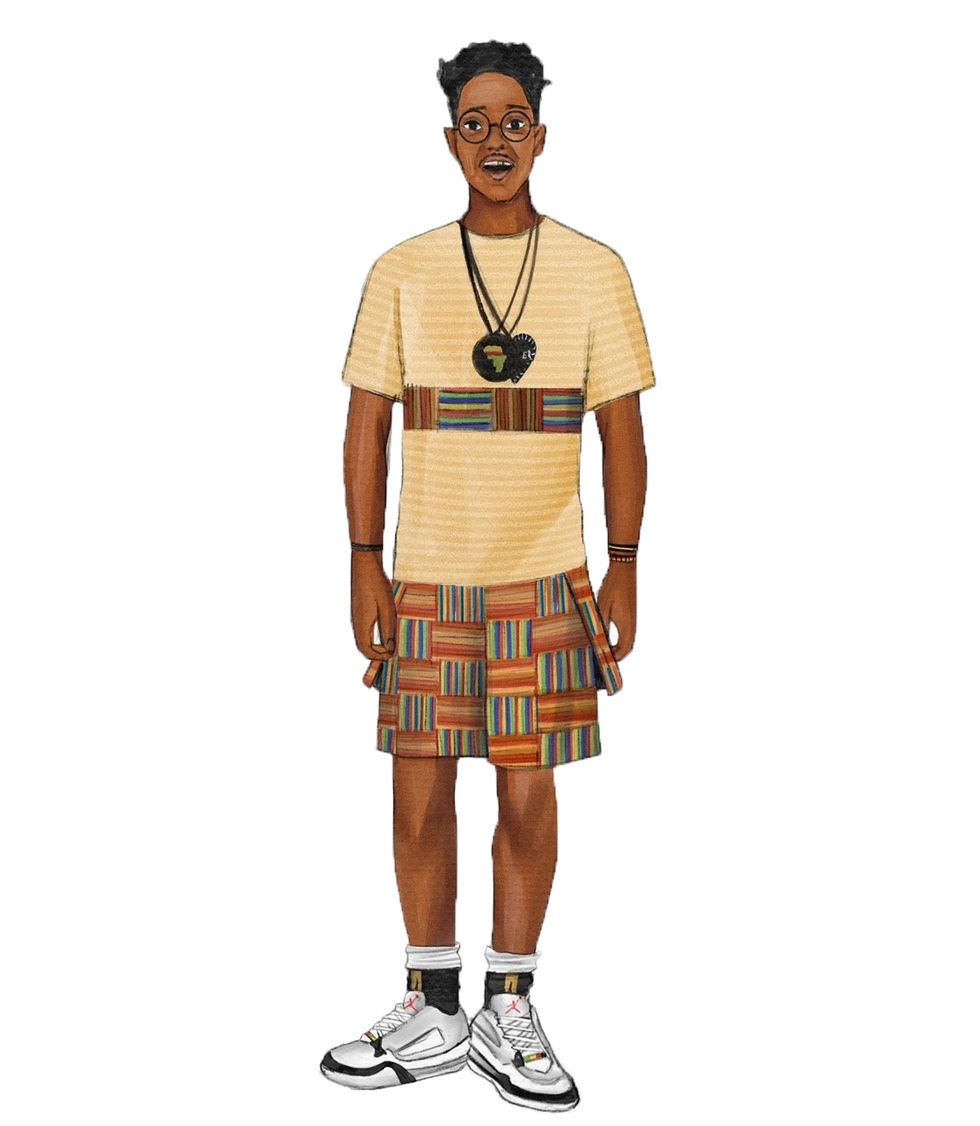

Buggin Out, Giancarlo Esposito

The protest begins with Buggin Out, the revolutionary, the harmless strange guy, the lone wolf. Buggin Out became the character who would connect the dots. We needed to show a radical boy, whose thick glasses and road-warrior attitude would make him unlike anyone and yet still a kid. The glasses are considered a prop. I know Giancarlo put in a heavy prescription to make him look bugged out!

I used bright Nigerian Kente cloth for his cargo shorts and yellow tunic as he walked through this film recruiting fellow protesters.

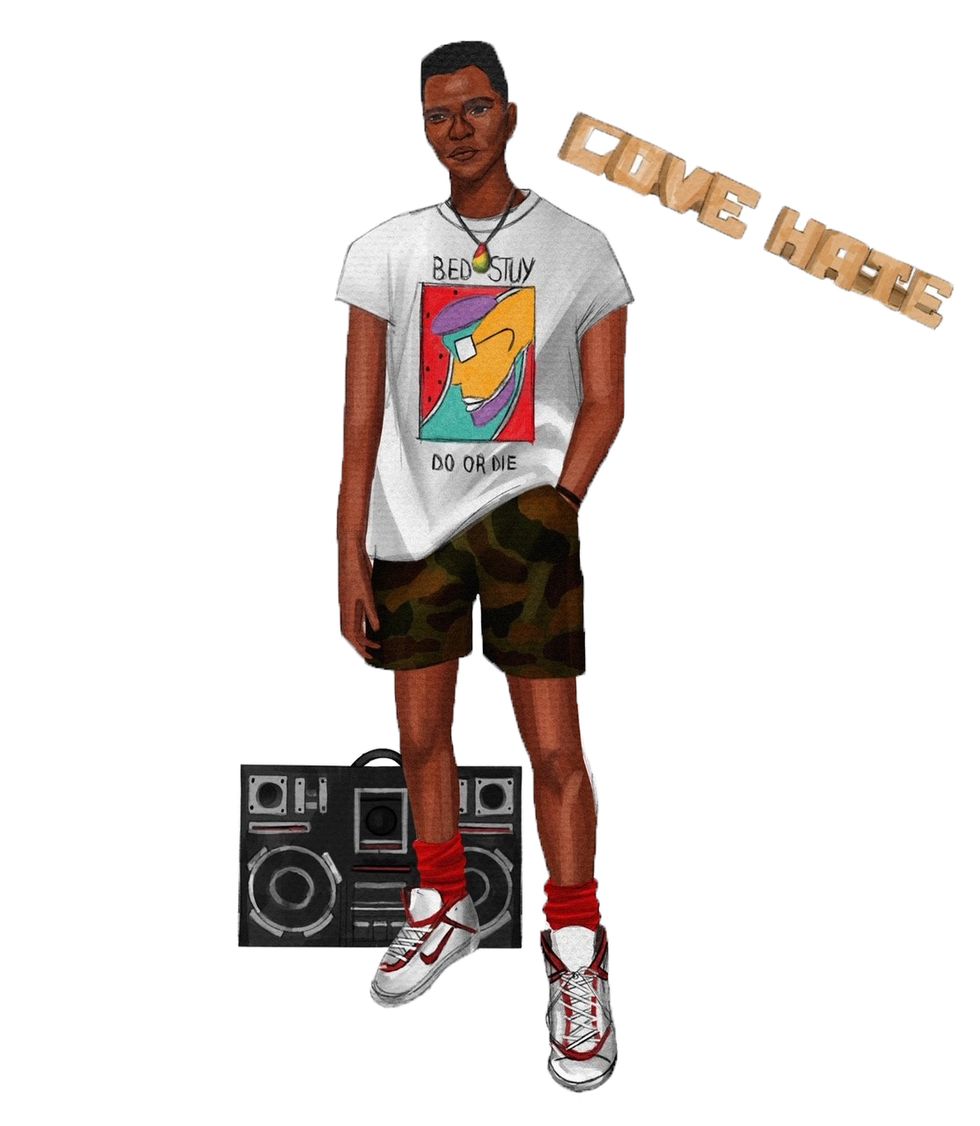

Radio Raheem, Bill Nunn

Radio Raheem becomes drenched in sweat as he recruits. His basic outfit doesn’t change, unlike the other characters’ outfits, and it shows the heat of the sun and his sweat. We didn’t change his clothes, because he doesn’t get wet when the fire hydrant is opened. (Everyone else in the neighborhood plays in the water, so they change their clothing.) His shoes were handpicked by our own sneaker head, Spike Lee, and were Nike Air Jordan 4 White Cements. On the front of the shoelace, I tied a wrist bracelet made using the colors of the Pan African flag.

I loved Brooklyn. It felt like a small city full of interesting people and neighborhoods. On Saturdays I would walk to the local Jamaican-food takeout joint or stroll Fulton and Flatbush, stopping in local shops. I noticed a cool bunch of T-shirts painted by local Brooklyn artist NaSha, and I really loved one of them, so much so that I asked her if she would paint the same shirt for Radio Raheem, with the saying “Bed-Stuy Do or Die.” The slogan was written in Spike’s script. To Spike, “Bed-Stuy Do or Die” meant “go hard or go home.” He said, “It signifies the hustle and resilience of the neighborhood’s people.” The local fashion scene in Brooklyn was fascinating to me. They seemed to be on the cusp of what was hip and what was cultural. NaSha made me the shirt.

When we first got the shirt on camera, I suddenly realized we had spelled Bed-Stuy wrong. I immediately went to 40 Acres editor Barry Brown. He showed me Radio Raheem’s first-day footage. I was saved—we hadn’t shot much beyond him walking away. I went back to NaSha to have the shirts repainted with the correct spelling. She had lived in Brooklyn all her life and hadn’t caught it either!

Excerpt from: The Art of Ruth E. Carter: Costuming Black History and the Afrofuture, from Do the Right Thing to Black Panther by Ruth E. Carter, published by Chronicle Books 2023