“In 2019, I had an epiphany,” says Virginia Johnson. For over a decade she’d served as the artistic director of Dance Theatre of Harlem, after being appointed to the role in 2010 by co-founder Arthur Mitchell. He had tasked Johnson with reviving the school’s professional company, which had disbanded in 2004 due to financial issues. Having completed that task and uniquely expanded the troupe’s repertoire, Johnson was ready to step down and welcome someone else into the role. “Being artistic director, I’ve had the opportunity to really look at what the company is about and why we exist, and it’s given me so much strength and energy during these past 12 years,” says Johnson, who postponed her exit until after the COVID-19 pandemic. “It’s been a great run, but we’re coming out of the darkness, and it’s time to move things forward with new leadership.”

June 30 marks Johnson’s last day at the helm of Dance Theatre of Harlem, at which point Robert Garland, who currently oversees its dance school, will take over. But Johnson’s legacy with the organization extends far beyond her tenure as artistic director. She was a founding member of Dance Theatre of Harlem, which choreographer Karel Shook and Mitchell, a former New York City Ballet principal dancer, established to create a place for dancers of color. Johnson remained with the company for an unprecedented 28 years, becoming one of its most illustrious principal dancers thanks to her flawless technique and effervescent stage presence. More importantly, she was an example to other dancers of color that there was space for them within the historically white institution of ballet. “One of the things that really touched me most in those early days was when Black dancers started coming into the studio and knew they belonged there,” she says. “Most of us were going, ‘Should I be doing this?’ But at Dance Theatre of Harlem they walked in and said, ‘I’m a ballet dancer. Of course.’”

Born in Washington, D.C., in 1950, Johnson began dancing as a young girl after a family friend opened a local ballet school, but it wasn’t until she saw London’s Royal Ballet perform Swan Lake while on tour in the capital that she became fully infatuated with the art form. “It was mesmerizing,” she recalls. “I was like, ‘That’s possible? I’m going to do that.’” At the age of 13, Johnson was accepted to the Washington School of Ballet on scholarship, becoming its only Black student at the time. “It wasn’t something that actually crossed my mind,” she says. “I was in love with ballet, and this is where I got to do it.” Still, when it came time for Johnson to graduate and go to college at New York University’s Tisch School for the Arts, the ballet school’s director pulled her aside and told her she would never get hired to dance because “there are no Black ballerinas.” “It certainly didn't stop me; I was like, ‘I’m doing this,’” says Johnson. “But if Arthur Mitchell hadn’t created Dance Theatre of Harlem, my teacher might have been right.”

More From Harper's BAZAAR

Formed in 1969, DTH began when Mitchell, who had initially been asked by the United States government to open a dance school in Brazil, decided instead to found a school in his home of Harlem in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. “That made him say, ‘I don't need to go to Brazil. I need to do my work here. I need to make a difference the way that Dr. King made a difference,’” says Johnson. “He wanted to teach the young kids here in Harlem life skills like focus, discipline, and perseverance that would be transformative and would enable them to break a cycle of despair. Nobody believed in those kids; they were forgotten.” Shortly after opening, the school welcomed 400 kids.

Johnson entered NYU in 1968, when the modern dance craze was at its peak, which meant she was one of only a handful of students who regularly attended the university’s standing 9:00 a.m. ballet class. Still, she missed her rigorous ballet training. “Then somebody said to me, ‘Arthur Mitchell’s teaching ballet classes up in Harlem on Saturdays. Why don’t you go up and take class with him, and then come back and do the real dancing?’” she recalls. Having previously taken a master class from Mitchell in Washington, Johnson was well aware of his cutthroat approach to teaching. But upon discovering his intentions to start a professional company, she began attending his classes as often as she could, and the next year was asked to be a founding member alongside five other dancers.

“I didn’t have the dynamics that he was looking for, and it took me a long time to get that kind of attack and musicality,” says Johnson, whose English style of ballet training differed greatly from Mitchell’s. He had trained under New York City Ballet co-founder George Balanchine, the father of neoclassical ballet.

The pressure Johnson felt was twofold: Not only did she have to recalibrate her training, but she was also a Black ballerina performing at the height of the American civil rights movement. “There was a lot of opposition to the Dance Theatre of Harlem; white people thought we couldn’t do ballet and Black people were saying, ‘You shouldn't be doing the white man’s art form,’” says Johnson. “We had to be very much focused on being excellent, being astonishing, changing people’s minds.”

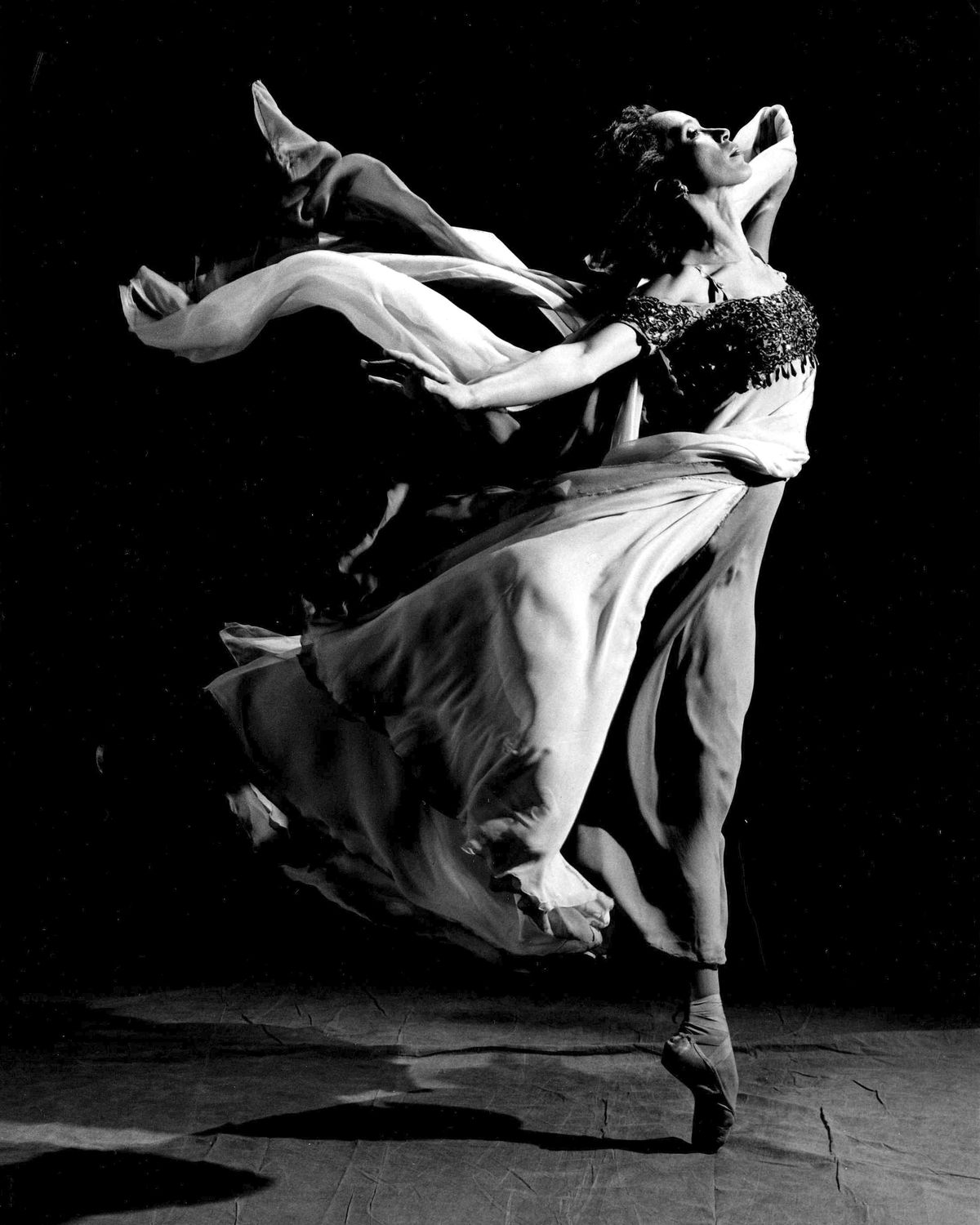

Along with a selection of Balanchine’s neoclassical masterpieces like Allegro Brillante, The Four Temperaments, and Agon, the company’s early repertoire included choreography by both Mitchell and Garland, also once a DTH principal dancer and the company’s first resident choreographer. “What made Virginia so enthralling to watch was her very, very, very clean pointe work,” says Garland. “And she could seamlessly go back and forth between neoclassical ballet and African-American vernacular dancing—it was a beautiful thing.” Amanda Smith, a dancer with the company since 2017, adds: “Anytime Virginia did anything, you saw the character she was portraying; she always embodied whatever she was doing.”

One of Johnson’s most captivating performances was in the titular role in Dance Theatre of Harlem’s Creole-inspired staging of Giselle, which transported the classic romantic ballet—about a young peasant girl who falls in love with a nobleman—from Austria to Louisiana. “We didn’t want to necessarily make people say, ‘This is an interpretation of something that you’re familiar with’; we simply wanted to present the ballet,” says Johnson, explaining that Louisiana, which began as a French colony populated by Black slaves and plantation owners alike, had a social structure similar to the Rhineland’s in the Middle Ages. “It was like, ‘Yes, we are Black, but we are not trying to put a Blackness to Giselle. We are trying to say we are human beings doing this art form.’

“I believed in the work that we were doing. I felt it was important for people to understand that ballet is an art form that belongs to everyone,” Johnson says, explaining why she stayed with the company for nearly three decades. “It does not always have to look the same. You don’t have to tell the same stories. It needs to reach people and touch them, and that is something that Dance Theatre of Harlem was always about: not just making pieces of perfection but making a vital connection with an audience.”

Upon retiring from DTH in 1997, Johnson started work on a communications degree at Fordham University, but was soon tapped to become the founding editor of Pointe magazine in 2000. Under her tenure, the publication focused on covering the ballet world from an insider’s point of view, featuring bourgeoning dancers like Misty Copeland and exploring what life and training was like for them. Nine years in, Johnson was fired from Pointe due to budget cuts—but, serendipitously, Mitchell reached out to her and asked her to take the reins at DTH as its new artistic director. “I was really terrified. How could I bring the company back?” says Johnson. “But the bare and simple point was that this was the man who gave me the dream I had dreamed, and I couldn’t say no.”

With funding help from foundations like Ford, Mellon, Rockefeller, Merck, and Duke, she was able to hold a national audition tour, ultimately signing 18 new company members, who began performing in 2012. “I wanted to continue the way that Arthur Mitchell had started Dance Theatre of Harlem, and show how diverse ballet could be as an art form, how many different kinds of things it could say, and how many different ways it could say it,” says Johnson, who notably commissioned pieces centering Black narratives and tapped female choreographers—who have long been in the minority—to set works on the company. “In ballet, you’re used to working with male choreographers," says Smith, "so it’s been nice to have the experience with women who have a different way of working, a different mindset, and also know how to dance on pointe.”

“Her job has been to revive and maintain the company, which has given me the opportunity to create ideas for my kids in terms of what they can aspire to,” Garland says. “My students know they’re aspiring to her.”

In April, DTH presented its 2023 New York season—Johnson’s last as artistic director and a sensational representation of her 21st-century vision for ballet. Along with a revival of Johnson’s favorite Balanchine work—the joyous Allegro Brillante—it included two New York premieres: William Forsythe’s Blake Works IV, which was choreographed over Zoom during the pandemic and set to synth-y electronic music by James Blake; and Sounds of Hazel by Tiffany Rea-Fisher, based on the life of Black jazz pianist Hazel Scott. “Nobody knows who Hazel Scott is,” says Johnson, explaining the musician’s place in history as the first Black person in America to have their own television show. “This is a story that we want people to know about, but it’s also a story that proves we have so much to say.”

Days after the season wrapped, Johnson was awarded the company’s prestigious Arthur Mitchell Vision Award at its annual Vision Gala, putting a bow on her incomparable career, which forever changed ballet. “I’m pretty overwhelmed, to be honest,” she says of receiving the accolade. “I look at how much bounty I’ve had in my life. I hardly need anything else. Just being here at Dance Theatre of Harlem from the beginning, having those experiences, having those challenges, having those wonderful, amazing opportunities—wow. It’s extraordinary.”